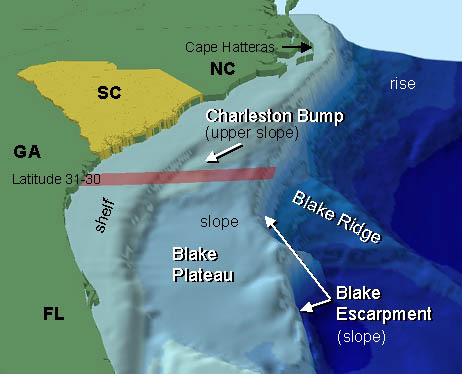

On Saturday and Sunday (30 and 31 July 2011) of my quick four-day trip to the Atlantic coast, we joined Brian Patteson on two of his famous pelagic trips out of Hatteras, North Carolina. Hatteras is the point of land in the U.S. that is closest to the Atlantic continental shelf and to the warm tropical waters of the Gulf Stream, so it is the best place to search for tropical seabirds.

NOAA image, accessed from wikimedia commons.

The first pelagic bird of the trip, a Cory's Shearwater, was a lifer for me, as were most of the species we saw on the open ocean. Craig Fosdick and I estimated a total of about 200 of this species on the first day and 100 on the second day, but we did not actually keep a count. In reviewing my photographs, I found that most of the 20 or so birds I photographed were of the Scopoli's subspecies, which breeds in the Mediterranean, rather than the borealis subspecies, which breeds in the Atlantic Ocean. Note the white tongues on the primary feathers, where a borealis bird should have primaries that are entirely or mostly black with small, diffuse white tongues at the most.

Two other shearwater species were much less common, but we estimated 10-30 of each of these on each of the two days. Audubon's Shearwater nests in the Caribbean and is the smallest shearwater regularly seen in North American waters.

Greater Shearwater breeds on islands of the southern hemisphere and migrates into our northern waters when it is not breeding. Despite its name, it seemed to me to be a little smaller than Cory's. My field guide says that it has a longer body, but a shorter wingspan.

The most common seabird species we saw was Wilson's Storm-Petrel. We estimated 300 or so on each day, but it was tough to make an accurate estimate because there were always a few of them following the boat. We were constantly watching out for other, rarer species like Band-rumped, Leach's, White-faced, or European Storm-Petrels, but I never saw any of these. (The trip leaders spotted two Band-rumpeds quickly flitting past the far side of a large flock of Wilson's, but neither Craig nor I were able to pick them out before they disappeared into the distant waves).

One of the highlights for me was also a specialty of this area, the Black-capped Petrel. This is the only regularly-occuring member of the genus Pterodroma in North American waters. It breeds in the Caribbean and forages in the Gulf Stream. We saw about 12 of these on our first day and about 20 on our second day.

By far the rarest bird of our pelagic adventures came on the second day. We had just come into a big flock of shearwaters and there were fish all around the boat. Others had told me that tropicbirds are attracted to activity of fish, boats, and other birds, and will often fly in high over the boat, so they can sometimes be missed if you're watching the birds on the water too closely. Each time we got into a situation like this, I tried to remember to also check the sky above us. As I peeked up from the shearwaters off the bow and looked behind me over the captain's wheelhouse, I saw the distinctive shape I was looking for. I yelled out, "TROPICBIRD!!!!" and before I could finish the word two or three other people were yelling the same thing. A beautiful adult White-tailed Tropicbird graciously made several circles around the boat before heading off towards the horizon.

All images copyright 2011 by Ryan P. O'Donnell except the illustration from NOAA.